The following is excerpted from Living in the Shadow of the Cross: Understanding and Resisting the Power and Privilege of Christian Hegemony, by Paul Kivel.

The language we use is an indication of the deep structures of the way we think. The vocabulary, phrasings, and both explicit and implicit meaning of English words and concepts reflect our long history and the influence of many cultures, religions, and ideas of both dominant and resistant groups.

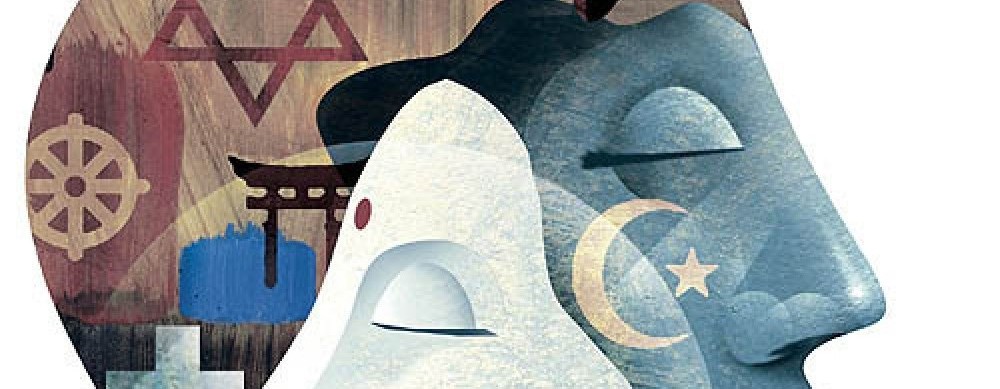

One of the longest-standing systems of institutionalized power in the United States is the dominant western form of Christianity that came to power when the Romans made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. Christian hegemony—the everyday, pervasive, deep-seated, and institutionalized dominance of Christian institutions, Christian leaders, and Christians as a group—has profoundly shaped our lives. Some of that influence is very visible in our laws, customs, beliefs, and practices. Other parts of that influence have become nearly invisible, secularized, “common-sense” forms of knowing and being in the world. One way to identify both levels is to examine our language and the ways it represents, reflects, and reproduces Christian dominance.

When presented with Antonio de Nebrija’s Spanish Gramatica, the first-ever grammar of any modern European language in 1492, Queen Isabella reportedly asked the scholar, “What is it for?” Nebrija reportedly answered, “Language is the perfect instrument of empire.”[1]

The ruling elites of Christendom well knew the truth of Nebrija’s statement. From the collapse of the Roman Empire to the Protestant Reformation and the introduction of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century, literacy was unavailable to the general population and only some Christian clergy could read and write. Mass was said in Latin which non-formally educated people could not understand. Modern European languages developed in a Christian dominated culture deeply influenced by Christian values. Many words which had Greek, Hebrew, Latin, Egyptian, or indigenous European roots were altered by Christian meanings.

Dominant western Christianity is based on a moral binary understanding of the cosmos. There is perceived to be a battle between that which is connected to God and good, and that which is connected to the Devil and therefore evil—everything lines up on one side or another. The original phrase in the New Testament is in Matthew 12:30, “He who is not with me is against me, and he who does not gather with me scatters.” This phrase was restated several times by former president George W. Bush and is a prevalent belief in our society. In this view there is no in-between, ambiguity, or compromise because the danger is too great. This moral “clarity” has become part of our everyday language.

The dominant influence of Christian hegemony and its moral binary worldview is perhaps most strikingly evident in the nearly constant ways that we judge things good or bad in our everyday conversations. Our constant referral to whether something is good or bad reflects the deeply binary way many of us see the world as well as the constant judgment we use to distinguish which is which. “That’s good,” “he’s a bad boy,” “She’s a good person,” we’re having bad weather,” “They are going through a bad period,” “We live in relatively good times,” “I’m sorry to hear about your bad news”—these are examples of phrases which are used to render an instant either/or judgment which we believe can be indiscriminately applied to all kinds of different phenomena.

The weather is not good or bad, it just is. Rain might be inconvenient, disappointing, or uncomfortable weather for some and might be welcome, needed, or comforting weather for others. Our simple judgment gives the weather a moral status and our binary shorthand lets us avoid actually describing the weather and acknowledging the personal and relative nature of the statements we make.

Similarly people are not good or bad. We are each complex and not easily summarized or dismissed by a judgment. We may do things that are illegal, immoral, unhealthy, or thoughtless, but that doesn’t make us “bad” people. And we know that “good” people are sometimes not what they seem. We often internalize both the judgment and the language to describe ourselves or feel as if we are good or bad people. This is reinforced by the media and the general culture that is quick to tell us which things count as good and which as bad.

We often also divide behavior into good and bad categories. There is good and bad sex (good sex = heterosexual sex for reproductive purposes, everything else is bad), good and bad violence (good violence is our violence against enemies, or the violence of the military or police—everybody else’s violence is bad), and good and bad torture (good torture is what we do to those who are evil, to terrorists and agents of the devil; bad torture is what others do to our troops and citizens). And, of course, many people speak of good girls and bad girls, usually referring to women who engage in behavior we either approve or disapprove of.

I’m not suggesting we abandon the use of the words “good” and “bad.” But it would help us communicate with each more effectively and caringly if we less often resorted to a simple moral judgment and instead described the world around us without the moral overtones. We would be more present and connected to the world and more able to acknowledge and respond to the complexity of ideas, people, situations, and even the weather.

Footnotes:

[1] J. Trend, the Civilization of Spain p 88 (1944) as quoted in Robert A. Williams, Jr. The American Indian in Western Legal Thought: The Discourses of Conquest. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990., p. 74.