The Crusades were a long series of religious wars spanning a period of nearly 600 years (1095 to 1699). They were crucial in the formation of a European (and subsequently western) Christian identity and have left a deep mark on western thinking. The word “crusade” is used for political and religious purposes (as when President Bush referred to our aggression in the Middle East as a Crusade,1 and even for secular ones (as in the Avon Foundation’s Crusade against Breast Cancer), but always resonates with images of good white Christian knights fighting against evil.

The crusades were a very complex phenomenon, both romanticized and condemned during different historical periods. During the Crusade era there were any number of alliances, wars, truces, and periods of relative peace between embroiled parties. The European and Eastern Orthodox churches, various Muslim, Arab, and Turkish rulers, Italian city-states, and secular European rulers were all guilty of violence and aggression. The longer the Crusades continued, the more Europeans solidified an identity as part of a Christian kingdom (Christendom) besieged by a monolithic Islamic empire seeking to destroy them. During the entire period the church tried to control the contours of Christianity in Europe (e.g. the Albigensian2 and Hussite Crusades3 ) and to manipulate secular politics in its favor. Various European rulers used the Crusades to jockey for wealth, land, and power both in Europe and in Western Asia.

Commoners, political and religious leaders, knights, servants, farmers, and tradespeople–every section of European society (and, of course, Muslim and Arab societies in West Asia) were affected by the centuries-long upheaval of constant mobilizations and war. Christianity and common Christian beliefs changed during this period and left residual patterns on future generations of Christian institutions and on our everyday culture and beliefs.

During this period Muslims were not united, a primary reason they lost control of Jerusalem. They did not border Latin Christendom, nor attack it, and there is little evidence Eastern Christians were under attack either. Islamic rulers were tolerant of Christians in Muslim-controlled areas throughout the Mediterranean basin. The first crusade was not a war of defense but an invasion to unite feuding Christians against a common enemy and to seize territory. It was the first European colonizing mission.

The Crusades were an unending series of holy wars because liberating land and people from rulers who were not Christian had no boundaries. In this sense, the wars defined Christendom not as a geographic space with a boundary, but as an ever-expanding righteous force in the world.

Within this framework, Musims were not convertible, but could only be eliminated. There was only “one right, one faith, and one law” (un droit, une foi, une loi)4 and Muslims were outside of all three. Therefore killing a Muslim (or a Jew) was considered not homicide but malicide (the killing of evil). The Crusades were a form of ethnic cleansing (cleansing the pagan dirt–spurcitias paganorum)5 and a precedent for the practice of ethnic cleansing for the next 1,000 years.

Identity as a member of Christendom was first given prominence during the reign of Charlemagne in the 9th century as he expanded the reach of Christian authority into a Holy Roman Empire. But it was not until the Crusades that people in Europe had a sense of themselves as members of geopolitical/religious community juxtaposed to another—that of the Muslims of West Asia. In fact, the Pope called for the first crusade partly to unify the fractious rulers of Europe into a common cause under religious control.

Previously, war had not been sanctioned with such explicitly religious justification. In 1096 Pope Urban II declared war not only justified but actually commanded by God. It became a religious duty and an opportunity to earn salvation. Each crusader made a solemn vow to deliver the Holy Land from Islamic control. Each “warrior” received a cross from a religious representative and was referred to as a soldier of the Church. There were material as well as spiritual benefits to being a crusader. Soldiers of the cross were granted spiritual “indulgences” in the afterlife, (ie., their sins would be forgiven if they killed a Jew, infidel or Saracen) because they were doing God’s work. They were also given temporal privileges, such as exemption from civil jurisdiction, canceled debts, freedom from taxes and tolls, and protection of their land and holdings. They were guaranteed eternal salvation if they died in the struggle against the infidel and therefore violence and death in the name of God became a source of grace.6

Previously, war had not been sanctioned with such explicitly religious justification. In 1096 Pope Urban II declared war not only justified but actually commanded by God. It became a religious duty and an opportunity to earn salvation. Each crusader made a solemn vow to deliver the Holy Land from Islamic control. Each “warrior” received a cross from a religious representative and was referred to as a soldier of the Church. There were material as well as spiritual benefits to being a crusader. Soldiers of the cross were granted spiritual “indulgences” in the afterlife, (ie., their sins would be forgiven if they killed a Jew, infidel or Saracen) because they were doing God’s work. They were also given temporal privileges, such as exemption from civil jurisdiction, canceled debts, freedom from taxes and tolls, and protection of their land and holdings. They were guaranteed eternal salvation if they died in the struggle against the infidel and therefore violence and death in the name of God became a source of grace.6

Centuries later Martin Luther would reiterate what this lack of responsibility would come to mean when he wrote, When acting with holy intention, the hand which bears the sword is as such no longer man’s hand, but God’s, and not man it is, but God who hangs, breaks on the wheel, strangles and wages war.” (quoted in Steele Micheal R. Christianity, the Other, and the Holocaust. Greenwood Press, 2003. p108.))

Built into these concepts was the understanding that Christians held the truth and they were commanded to force others to accept that truth or die. For example, a main target of the Crusades became the substantial Jewish communities throughout Central and Eastern Europe that were encountered by the Crusaders on their way to Jerusalem. There was a long history of anti-Semitism against Jews within the church, originating in the Gospels’ claim that Jews killed Jesus. Therefore, it did not take much stirring up to convince Christians it was necessary to deal with Jews on their way to save the Holy Land from other infidels who they had far less knowledge about. As they swept east wearing crosses on their clothes, engaged in holy battle for Christ, they challenged the Jew in the towns and villages they passed through with a simple command, “Convert or die.” Many times they simply killed all the Jews. At other times they let the few Jews who converted live. In some towns the entire Jewish community chose to commit collective suicide rather than be killed. Tens of thousands of Jews died beginning with the very first months of the first Crusade in 1096.

When the Crusaders arrived in Jerusalem and finally succeeded in taking the city (the only Crusade that ever reached the city) they promptly killed nearly every non-Christian who hadn’t been able to flee, of whatever age or background. Even conversion was no longer a choice offered. The cross became a symbol of terror for Muslims and Jews and of pride and power for Christians.

The Crusades focused to the east continued until the end of the seventeenth century when the final crusade was settled with the Treaty of Karlowitz in 16997

The wars waged by the Church and its secular Christian allies against the Moors from the 11th through the sixteenth century were also considered part of the crusades. In the north of Europe crusades were organized against the Prussians and Lithuanians. The wars against the Cathars were an official crusade and the popes also declared crusades against powerful individual rulers in Europe.8

The Crusades brought many changes to Europe and Christianity during a period in which the church was again consolidating its power, extending its geopolitical reach throughout southern Europe, and reestablishing orthodoxy within its own ranks.

Beginning with the first Crusade, violence was defined as a sacred act. The Crusade was launched by Pope Urban II with the battle cry of “God Wills it!” Up to that time Christian theology had placed the resurrection of Jesus and the incarnation as central to the meaning of God’s actions. As part of the crusaders’ religious rhetoric, the crucifixion became increasingly important. The violence of the crucifixion and martyrdom of Jesus reinforced the idea that violence and human suffering were sacred and led to salvation.

During the crusades, a new role was created for men as a knight or spiritual warrior whose duty was to protect and rescue any good under attack from evil. Military orders of religious knights like the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, owing obedience only to God, were sworn to protect and rescue women, children and Christendom.

The violence of the Crusades soon turned into war against any kind of difference. Over time the enemy shifted, but was always identified with evil; there was no end to the burden and responsibility of a Christian warrior. Just as God would protect the knight, he would succeed in protecting the vulnerable from infidels, heretics, dragons, Jews, heathens, women–anyone considered an agent of the devil. Inquisitions began during this period. Spain was conquered from the Moors. The period of colonization began. Christianity forced itself into the everyday beliefs and practices of Europeans, rich and poor alike and forced itself on every people it encountered.

The violence of the Crusades became emblematic of a new militant and expansive Christianity that provided the foundation for western colonization of the rest of the world. Thereafter, war could be declared against any kind of religious, political, or even cultural difference within Christianity itself. There were attempts throughout Europe to extend the practice of Christianity into peasant life and to eliminate all forms of resistance to Christian hegemony. Killing savages, infidels, and heretics for Christ became a legitimate form of redemption.

As religious historian James Carroll has written, the crusades were “a long series of military campaigns, which, taken together, were the defining event in the shaping of what we call Western civilization. A coherent set of political, economic, social, and even mythological traditions of the Eurasian continent…grew out of the transformations wrought by the Crusades.”9

By the end of the Middle Ages the word crusade had come to refer to all wars undertaken in pursuance of a vow and directed against infidels, or those under the ban of excommunication.

The colonizing invaders, who since the fifteenth century had been going forth from Portugal and Spain to “discover” new lands, considered themselves to be soldiers of the cross on holy crusades. The Infante Don Henrique (Ruler of Portugal), Vasco da Gama, and Christopher Columbus, among others, wore the cross on their breast and on their sails. In addition to commercial goals, they were considering possibilities for attack on Islamic rulers from the rear by circumnavigating Africa or reaching Asia. The popes, in a series of Papal Bulls, strongly encouraged and blessed these expeditions.

The US military seems to have confused the Biblical canon with the war cannon.

Echoes of the Crusades continue to haunt our lives, usually to justify political, religious, or economic aggression by marshaling our attention towards some common, demonized enemy. Although the enemy changes and the rhetoric is somewhat secularized, it is still used to rally support by appealing to historic Christian values of sacrifice, aggression, proselytizing, anti-Islamic, anti-Jewish, and anti-pagan beliefs, as well as divine mission.

For example, in 1916 during World War I, British premier, David Lloyd George stated that “Young men from every quarter of the country flocked to the standard of international right, as to a great crusade10.” A British clergyman added, “Not only is this a holy war. It is the holiest war that has ever been waged…[The pagan god] Odin is ranged against Christ. Berlin is seeking to prove its supremacy over Bethlehem.”11.

In World War II, the allied invasion of Europe was called Operation Crusader and General Dwight D. Eisenhower told his troops, “Soldiers, sailors, and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, you are about to embark on a great crusade.” He subsequently titled his memoirs of the war Crusade in Europe and wrote, “This war was a holy war, more than any other in history this was has been an array of the forces of evil against those of righteousness ((quoted in Carroll, Crusade)).”

During the 1950s, people in the United States commonly referred to the crusade against communism. As the U.S. expanded its empire and tried to drum up anti-Soviet sentiment, the Soviets were often described as communist, as evil, and as godless. As the war wound down, the religious overtones of the struggle were evident as the public relations battle to convince people in the U.S. to take the Soviet threat seriously was increasingly couched in terms of the threat from godless communism.

Subsequent military engagements in Guatemala, Iran, Vietnam, Nicaragua, Laos, China, Eastern Europe, and many other places were justified in the name of this cosmic struggle against, as Ronald Reagan called it, “the evil empire.”

The same pattern continued as President Bush and his surrounding entourage talked about the “axis of evil12 and our crusade against terror. “This crusade, this war on terrorism…” he declared13, a couple of days after the events of 9/11 on September 14, 2001. Significantly this declaration of war14 was announced at a prayer service in a National Cathedral in Washington.

The first warrior pope, Gregory VII said, “Anyone who is not in accord with the Roman Church should not be regarded as a Catholic.” ((Carroll: Crusade, p 282))

George W. Bush declared, “Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists.”15

A product currently available.

The use of the word crusade continues to denote a rallying cry to join an aggressive battle against something evil, whether or not it is in a religious context.

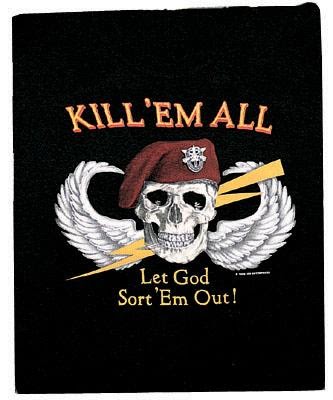

The idea of “Killing them all” and leaving it to God to sort out the souls of the dead is a popular one among traditionalist Christians. “Kill all, kill all. The Lord will know His own,” said a military leader during the Albigensian Crusades. And indeed it is characteristically Christian. It only makes sense to those who believe in heaven and an afterlife. The phrase would be meaningless to an atheist. It is not difficult to find Christians today who espouse such views. Devout believers in US military units including Marines, Army Rangers, and Special Forces favor a slightly different formulation “Kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out.” This phrase is found printed on t-shirts sold on military bases. The phrase even serves as an unofficial motto for some organizations in the US police and military. A Google search for “Kill ’em all” returns thousands of matches – many for the sale of these caps and t-shirts.

Conclusion

The last crusade was fought over 300 years ago but the battle cry hasn’t diminished. We are currently involved in military attacks on seven different Muslim countries and have a national travel ban against Muslims from many countries in place. Describing people and countries we have differences with as evil still marshals popular support for almost any military aggression. “Kill them all and let God sort’Em Out!” is still a popular slogan on t-shirts and hats for Christian men inside and outside of the military. We can’t continue to let our political leaders manipulate us into supporting constant war and devastation under the assumption that we are the righteous warriors and other peoples are evil and dangerous. Our dominant Christian history of violence is long and deep and we can only stop our current aggression by understanding its popular roots.

APPENDIX

Organizations and Campaigns

Avon Foundation Breast Cancer Crusade

The mission of the Avon Foundation Breast Cancer Crusade is to raise funds and awareness for advancing access to care and finding a cure for breast cancer, with a focus on the medically under-served. From its launch in 1992 through 2005, the multi-faceted initiatives of the Avon Breast Cancer Crusade have raised and returned more than $400,000,000 to the breast cancer cause worldwide.

Campus Crusade for Christ International

Campus Crusade for Christ International is an interdenominational ministry committed to helping take the gospel of Jesus Christ to all nations. We cooperate with millions of Christians from churches of many denominations and hundreds of other Christian organizations around the world to help Christians grow in their faith and share the Gospel message with their fellow countrymen. Working together with these fellow believers, our goal for this decade is to help give every man, woman, and child in the entire world an opportunity to find new life in Jesus Christ.

Note: Recently, the name Campus Crusade was astutely changed to Cru, which elicited a backlash against “political correctness” by its supporters.

Others

There is the World Literacy Crusade, the crusade against AIDS, churches and ministries that still use the term “crusade” in their official name and even a few humanitarian organizations.

some of the many Crusade themed books

Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War by Rick Atkinson

Crusade by David Weber and Steve White

Science Fiction, and Crusade: Let My People Go by Jefferson Scott (a novel about Christian commandos who fight off Muslim raiders in Southern Sudan)

Vanguard of the Crusade: The 101st Airborne Division in World War II by Mark Bando Living in God’s Love: The New York Crusade by Billy Graham

Last Crusade: Spain 1936 by Warren H. Carroll

New Labour’s Foreign Policy: A New Moral Crusade? by Richard Little, Mark Wickham-Jones

Churchill’s Crusade: The British Invasion of Russia, 1918-1920 by Clifford Kinvig

- Waldman, Peter and Hugh Pope. “‘Crusade’ Reference Reinforces Fears War on Terrorism is Against Muslims.” NYT. 21 Sep 2012. [↩]

- “The Albigensian Massacre. Episode 9: Lineage.” Lineage Journey on YouTube. 15 March 2017. [↩]

- “Battle of Lipany: Hussite Wars 1419-1434.” Kings and Generals on YouTube. 4 March 2018. [↩]

- Mastnak, Tomaz. Crusading Peace: Christendom, the Muslim World, and Western Political Order. University of California, 2002. p124. [↩]

- Mastnak, p128 [↩]

- Carroll, James. Constantine’s Sword: The Church and the Jews, A History. First Mariner Books, 2001. p 240 [↩]

- Treaty of Karlowitz, January 26, 1699, Congress of Carlowitz, National University of Singapore archives. [↩]

- Bréhier, L. “Crusades.” New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia, Robert Appleton Company, 1908. [↩]

- Carroll, James. Crusade: Chronicles of an Unjust War. 3 August, 2004. Holt, p 4. [↩]

- Darian-Smith, Eve. Religion, Race, Rights: Landmarks in the History of Modern Anglo-American Law. Bloomsbury, 2010. [↩]

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press, 1995. [↩]

- “George W. Bush describes Iraq, Iran and North Korea as ‘axis of evil’” History.com. 27 Jan 2020. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/bush-describes-iraq-iran-north-korea-as-axis-of-evil. [↩]

- Waldman [↩]

- Carroll, James. “Lessons to Be Learned from the Afghanistan Papers.” The New Yorker. 12 December 2019. [↩]

- Bush, George W. “State of the Union Address.” 11 September 2001. [↩]