The following is excerpted from Living in the Shadow of the Cross: Understanding and Resisting the Power and Privilege of Christian Hegemony, by Paul Kivel.

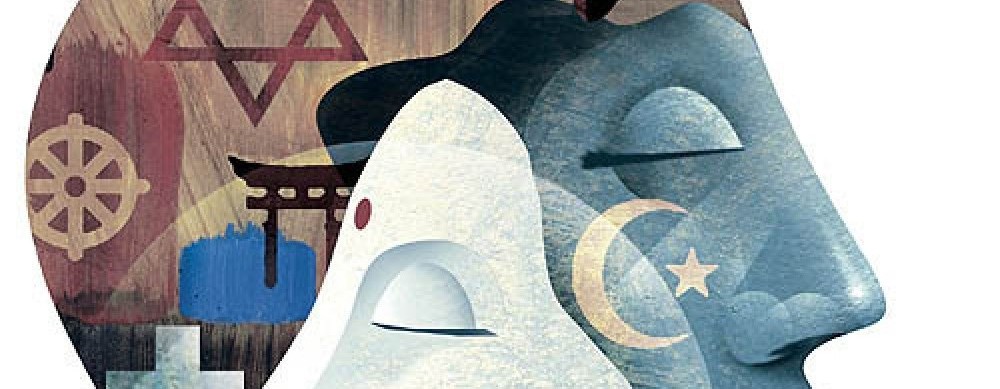

A narrative is a pattern of story telling used to explain the world and compel people to action. It assembles, collects and repeats stories, shaping them to convey values to the listener/reader. The narratives described below, all used for over a thousand years to prescribe a specific worldview, are repeated today in everything from sermons and news stories to movies and children’s cartoons.

Conversion Narrative

Many of the values clustered around the belief humans are sinful and must find God to be saved fit together in a conversion narrative. Even before Augustine’s Confessions, Christians wrote about how they had been sinners who lost their faith, abandoning God, until they saw the light and were saved by his grace. In early US Colonial times, such influential preachers as Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards wrote similar confessions about how they had found their way from sin to salvation. Sunday services were filled with ordinary Christians who confessed their sins and accepted grace, allowing them to become church members regardless of past behavior. An entire vocabulary became associated with these experiences, including concepts of sin, evil, guilt, blindness, darkness, despair, confession, grace, seeing the light, repentance, redemption, penance, healing, release, testifying or witnessing, acceptance of God, salvation and a new life of joy. Once they committed themselves to God, those saved took on the obligation to save others.

Today, twelve-step programs follow such a conversion narrative. A person is a sinner/alcoholic until they give up control to God/a higher power and let God’s grace into their life. They are then saved and on the road to recovery. Temptation, however, is only a drink away. The constant presence of temptation is also part of the conversion narrative.

The US criminal legal system gives a special, mitigating force to self-conversion of a criminal: judges see confessions of guilt as indications that the indicted have seen the evil of their ways. These indications may be affirmed by an evaluation of a prisoner’s charitable acts/good behavior and result in plea-bargaining, a reduced sentence or early parole.

Racial conversion narratives are another example of how this deeply engrained framework manifests in our culture. As historian Fred Hobson has described, racism has been called a social problem, a disease (sometimes a cancer), a poison but “most often it has been described by those writers who have examined it in very personal terms as, simply, ‘sin’ or ‘evil.’”9 White Christians like Lillian Smith, Larry King,10 and scores of others11 who became anti-racist activists have confessed to racial sins such as moral blindness and complicity with an evil system. Sometimes their message to other white people has shifted from “stand up and fight against racism” to “repent and see the light” just as they have. They may be too secular to say “Come to Jesus,” but the message can sound similar. Oftentimes other whites see them as saints (even though people of color are rarely so sanctified for their own anti-racist efforts). As historian Hobson suggested, for white racial converts, “… the Civil Rights Movement was about much more than race. It was about personal and cultural salvation in a broader sense.”12

The song “Amazing Grace” is probably the most well known conversion narrative. Written by a slave trader who came to see the sinfulness of slavery, the song tells of his redemption. The song has been recorded thousands of times, is sung literally millions of times a year and is possibly the most popular folk hymn of all time.13

Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound,

that saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost but now am found,

was blind, but now I see.14

Although slave-trading Captain Newton’s personal redemption is enshrined in the song, there is little acknowledgment of what he did during his years of slave trading, or of the enduring impact that slavery had on millions of African-Americans.

Currently as well, many white people can have a personal revelation about what some call the evils of racism; the experience might be very powerful and change how they understand racial injustice and their complicity with it. Unfortunately this experience does not always lead to work for racial justice. Personal transformation can be so important it becomes all that matters. Challenging the continuing operation of racism may not feel as imperative in comparison.

Or, conversely, they may think their task is to get other whites to have a similar conversion experience. They then take on the role of missionary – trying to convert as many white people as possible to save them from the sin of being racist.

The Jeremiad

The key story of a paradise lost in Western culture is the story of Adam and Eve and their fall. This story’s central role in Christianity is not simply to describe a mythical fall but also describe human sin, women’s culpability and the degenerate nature of society. The longing for highly romanticized and idealized times are long-standing currents in Western literature and art, especially romantic portrayals of Greek, Roman, Native American, pre-modern and non-western societies.

More commonly, such nostalgia15 is expressed as a yearning for the good old days, simpler times when life is projected to have been better. Agrarian life, the time of the so-called Founding Fathers, the days of the frontier, the 1950s, 1960s or our childhoods – whether we believe we can get back there or not, few of us are immune to the appeal of some former period. Many people want to believe that community, religious faith or deference to traditional values once characterized society.

Jeremiads, named for the rhetorical style of the biblical Jeremiah, are narrative assaults on existing society held to be corrupt, with appeals to return to days of former glory. Sometimes referred to as lamentations of decline, they involve the invocation of a prior, more virtuous period – a golden age with righteous leaders -from which we have fallen. A jeremiad commonly contains a listing of current sins or signs of decline, an exhortation to repent, a promise of restoration and forgiveness and is usually coupled with a prediction of dire consequences if we don’t change our ways.

The jeremiad is a pervasive rhetorical device used by both political and religious leaders to evoke the belief we cannot claim the future without reclaiming some (often false, highly selective or sanitized) version of the past. As political science professor Andrew Murphy has written, “… the story of American moral decline and divine punishment has served as a powerful tool for political mobilization throughout the nation’s history…”16 However, the exhortation to return to the past will generally distract us from developing collective principles and practices we need to solve today’s challenges.

Captivity Narrative

The August 9, 2010 cover of Time magazine portrayed a grisly picture of an Afghan woman whose nose has been cut off. The caption on the cover read “What Happens if We Leave Afghanistan.”17 This cover appealed for political support of a war which claimed to rescue Afghan women supposedly held captive by Afghan men, specifically the Taliban.

In captivity narratives other cultures are barbaric and oppressive and Christian ones are civilized and must act as rescuer. Conveniently overlooked is the complicity of our culture in the history of colonization contributing to oppressive conditions and the opportunistic way strategies of intervention are imposed.

From stories of Christian knights rescuing the Holy Land and damsels in distress to Disney movies of princely heroes rescuing sleeping beauties, The Christian West has long told stories of “innocent women and children” under threat by some supposedly uncouth band of men or other evil force. Early frontier stories of white Christian women (and sometimes missionaries) being captured by Native Americans are a precedent to contemporary admonitions that Christians have a moral obligation to invade dangerous lands, fight infidels and rescue the women in enemy hands. Versions of captivity narratives are also used to reinforce control and punishment of domestic groups labeled as Other in the US. For example, the myth that African-American men are physically and sexually dangerous to white Christian women who therefore need protecting by white Christian men (only assumed to be safer for them) was one justification for lynching and is currently used to rationalize high levels of racial profiling and incarceration.18

The use of captivity narratives is particularly evident when social problems are identified which threaten the innocence of the presumed pure: women and children – and beyond them, presumed innocent members of any group we are members of, for example American citizens who were casualties of 9/11. We then become quick to identify a group of the devil’s agents whom we then target for public scorn, state control or outright war. Such moral panics occur especially in times of political and economic uncertainty: depressions, periods of increasing inequality of wealth or high immigration. At such times, ruling elites try to direct attention to some group designated as threatening the moral fabric of society. The list is constantly changing and never-ending: Muslims, communists, immigrants, terrorists and a host of others. The implied dangers appeal to deep-seated beliefs that women and children (or by extension citizens) are innocent and corruptible, that white Christian men can protect them and that such dangers are a normal, accepted and even expected part of any social landscape.

The captivity narrative is based on dualism and echoes the cosmic battle between good and evil. It consistently sets up Christian men as moral, clearly differentiated from them (any number of Others wanting to destroy us). Women are often the passive, voiceless victims (or pawns) in captivity scenarios. Chinua Achebe described the “out there,” the “dangerous frontier,” as “a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognizable humanity into which the wandering European enters at his peril.” One could easily substitute Christian for European to encapsulate the savior myth.19

When a Christian or Christian nation enters voluntarily into such a perceived terrain on a mission to save or help, they reinforce an illusion of benevolence and reluctant acceptance of the white man’s burden. Rescued frontierswomen in Westerns and princesses in movies can be portrayed as grateful for their rescue. The citizens of Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq cannot; the illusion of benevolence cannot be maintained in the real world.

Women do face severe challenges in many countries. In complex situations it can be difficult to know how to be allies to those living under oppressive conditions. However invoking a captivity narrative to justify armed intervention that then leaves women in worst political and economic conditions is hypocritical and unjust. The hypocrisy is more pronounced when the US did not claim any interest in the women of Afghanistan over the years it was arming the Taliban, nor in the dire straits today of women in the Congo.

Traditionally, the US has labeled Communist rulers, evil dictators and sinister warlords – all supposedly holding their populations hostage – as the evil enemy and have declared war against them. More recently, US ruling elites have shifted to phrases such as humanitarian intervention and peacekeeping to describe these relations of rescue. The opportunism of such military actions – although apparently justified by reference to civilized values, rescue of subjugated populations and the evil of our opponents – remains the same.20

We Need a Savior

From the belief that people and populations are held hostage to evil can follow the notion they need a savior to rescue them. Whether in the children’s book series the Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis; movies such as Avatar or Crazy Heart; the popular Hollywood trilogies Star Wars, The Matrix or Lord of the Rings or the hopes so many pin on the next presidential candidate, North American culture is filled with examples of Christian-derived savior figures.

When people believe they need a savior, whether God-sent or not, they are likely to devalue their own ability to bring about change. Individuals can also play out a savior syndrome in their own lives: seeing themselves in the role of hero to those less fortunate. White-teacher-to-the-rescue movies such as Dangerous Minds, The Ron Clark Story and Music of the Heart are based on this syndrome. The behavior of a teacher, social worker or other public employee who considers themselves both morally superior and burdened by caring can undermine the dignity and autonomy deserved by those seeking services. People who see themselves as well-intended saviors often end up being enthusiastic participants in systems that perpetuate various kinds of oppression. When they fail to transform those around them, they can blame failure on those we label unresponsive individuals rather than social systems.

The savior is represented most iconically as a lone Christian knight, soldier or superhero but can also take the form of a missionary, revolutionary or doctor. They are usually men, rescuing and protecting women and children or victims of dictators and barbarians. Generally, they wear white. White women can substitute for men in the role of saving people of color, especially youth. US media and literature is so replete with these tales of capture and rescue, protection and defense, revenge and punishment it is difficult to find exceptions.

The necessity for saviors, coupled with beliefs in the United States’ exceptionalism and manifest destiny, has leads many people to assume that the US is a nation that can and should save others. Our victories certify God’s approval and the sanctity of our acts. Our violence has often been labeled redemptive because it redeems the world from evil as well as redeeming those who participate in the so-called cleansing. In this salvation narrative, soldiers are killing people who need to be killed because they are dangerous and unredeemable. No matter how many were murdered in the process, we are taught the US saved the Vietnamese, Afghanis and Iraqis. The more we tell stories of the great white male leaders who saved us in times of crisis, the more we falsify history and encourage contemporary passivity.

Footnotes:

9. Fred Hobson. But Now I See: The White Southern Racial Conversion Narrative. Louisiana State University, 1999, p. 16.

10. Larry King. Confessions of a White Racist. Viking, 1971.

11. See Hobson’s But Now I See for a detailed look at narratives from US southerners.

12. Hobson, But Now I See, p. 108.

13. Jonathan Aitken. John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace. Crossway, 2007 and Steve Turner. Amazing Grace: The Story of America’s Most Beloved Song. HarperCollins, 2002.

14. “Amazing Grace” by John Newton quoted in Hobson, But Now I See, p. ix. This bodily metaphor is also, of course, profoundly disparaging of the wholeness and integrity of people with disabilities.

15. Nostalgia is “[a]n affective state characterized by positive, yet bittersweet, associations with some aspect of the personally experienced past”: Andrew R. Murphy. Prodigal Nation: Moral Decline and Divine Punishment from New England to 9/11. Oxford, 2009, p. 131. Arthur Dudden describes nostalgia as “a preference for things as they once were, or, more importantly, a preference for things as they are believed to have been.” Arthur P. Dudden. “Nostalgia and the American.” Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 22#4 (October-December 1961), p. 517.

16. Murphy, Prodigal Nation, p. 111.

17. The cover statement did not include a question mark, leaving the reader to conclude that barbarous violence against women is the only thing that can happen if we withdraw.

18. For an egregious example of the impact of these beliefs on the lives of young men of color see: Sarah Burns. The Central Park Five: The Untold Story Behind One of New York City’s Most Infamous Crimes. Vintage, 2012.

19. Achebe used the word European instead of Christian in the original, quoted in Sherene H. Razack. Dark Threats and White Knights: The Somalia Affair, Peacekeeping, and the New Imperialism, 2nd ed. University of Toronto, 2004, p. 7.

20. For a discussion of humanitarian intervention see Bricmont, Humanitarian Imperialism. For a look at peacekeeping missions see Razack, Dark Threats. For an insightful look at how recent Western documentary films such as Half the Sky frame their stories in captivity narratives see Richa Kaul Padte.“Half the Story: When Will Western Documentaries Realize They’re Using the Wrong Lens?” bitch, Issue #57 (Winter 2013), pp. 43-5.