- Via sunnewsnetwork.ca

Holidays are great when they reaffirm our connections to family and friends, are inclusive, build community and honor accurate histories. Holidays are also important when they celebrate significant cultural events and connect us to our deepest communal values.

However, holidays can be destructive when they celebrate war or colonialism, are promoted aggressively or when corporations use them to promote values hostile to our environment and communities. Holidays become destructive and exclusive when they are proclaimed as universal but are actually culturally specific or when they are based on historical lies and perpetuate misinformation. We need to think seriously about what we celebrate and why, who is included or excluded in the celebration and what values are implicitly or explicitly communicated.

Christian leaders have established an annual holiday cycle that extols US militarism/triumphalism, the nuclear family, consumerism and whiteness. This holiday cycle downplays the violence in our history and holds up a few white Christian men, such as Christopher Columbus and our presidents, for uncritical praise while emphasizing faith, family and country.

For many in the US, this cycle has come to seem traditional even though most of the holidays originated within the last 150 years. For some, these holidays have come to feel familiar, unifying and just plain American even though for millions of others they can be painful and alienating. Most of our national holidays are seen as secular, even though their underpinnings are deeply Christian. Even Christmas and Easter are viewed as secular by many. (I have been told that the phrase “Merry Christmas” in bold letters on the public buses in my city is not religious but merely a general holiday greeting.)

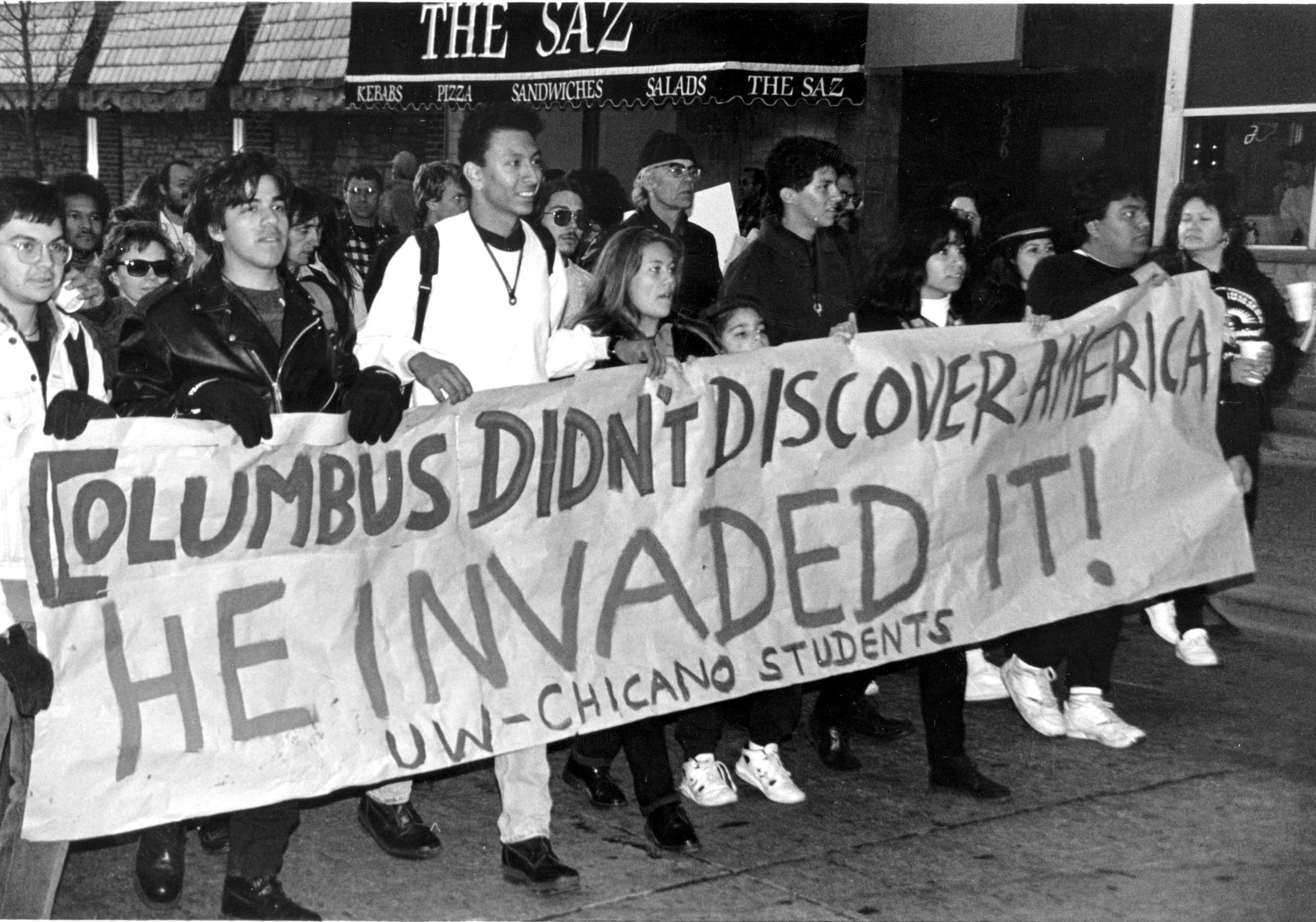

Columbus Day

Even by the standards of his day, Columbus was an extreme Christian who saw his voyages as attempts to meet up with the kingdom of Prester John (a mythical Christian ruler in east Africa) and from there reconquer and rebuild Jerusalem.

- Via Tumblr

Brutal in his suppression of Native Peoples, Columbus condoned rape of Native women and hung rebellious infidels in groups of 13, the number representing Jesus and his apostles. In a letter to the Spanish court dated February 15, 1492, before his departure, Columbus clearly delineated his goals: “to conquer the world, spread the Christian faith and regain the Holy Land and the Temple Mount.”[1] “Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold.”[2] Those indigenous peoples who were not enslaved were killed. The population of Haiti at the time of Columbus’s arrival was between one and a half million and three million. Sixty years and five Columbus expeditions later, nearly every single Native had been murdered.[3]

During his voyages Columbus was carrying out Papal policies of discovery that gave him divine sanction for the theft of Native lands and the destruction of Native peoples on the grounds that they were not Christian. Even his economic motives had religious undertones. He wanted to discover riches so that the rulers of Spain could afford a new crusade to reclaim the Holy Land. In addition, his voyages were probably, at least partially, funded from wealth stolen from Jews when they were expelled from Spain in 1492 to create a pure Christian kingdom.

Halloween

Continuing Christian efforts to curtail non-Christian community rituals, in the eighth century Pope Gregory III moved All Saint’s Day from the spring to supplant the Celtic holiday, Halloween (originally the pagan holiday Samhain), which celebrated the harvest and preparation for winter.

Catholic Irish immigrants brought many of the current customs practiced on the holiday to the US during the Great Famine (1845-1852). Traditional Halloween figures include the devil, demons, witches and black cats, all associated with evil by Christianity. Even the name jack-o’-lantern can be traced back to the Irish legend of Stingy Jack, a greedy, gambling, hard-drinking farmer who tricked the devil into climbing a tree and then trapped him by carving a cross into the tree trunk. In revenge, the devil placed a curse on Jack, condemning him to forever wander the earth at night with the only light he had: a candle inside a hollowed turnip.

Thanksgiving

Like Columbus Day, Thanksgiving is a holiday that attempts to give a benign veneer to a violent colonization process. Early New England colonists generally believed Native Americans to be infidels and Canaanites. Puritan preachers in the colonies routinely referred to them as savages.

The historical evidence is not of a thanksgiving meal but of an invitation from the invaders inviting Wampanoag locals to a feast with the goal of negotiating a treaty for land the Puritans wanted. The Wampanoag brought food to the gathering out of a sense of hospitality.

The Wampanoag and other Natives refused to give up their lands, but the pressure and violence from the colonists were unrelenting. Within a single generation the Puritans eliminated nearly all Native peoples in New England by murdering them, driving them into French territory as refugees or selling them into slavery in the Carolinas.[4]

Thanksgiving, as celebrated today, promotes a false understanding of this period in which white Christians supposedly coexisted peacefully with Native Americans. It portrays Indians as generous but long gone, mysteriously vanished from the places the so-called pilgrims lived and where their descendants live still.

For the Puritans, a thanksgiving was a religious holiday in which they would go to church and thank God for a specific event, such as the winning of a battle. Many of their early thanksgiving celebrations were to give thanks that they had triumphed over “the Indians” and been able to massacre so many.[5] This is illustrated in the text of the Thanksgiving sermon delivered at Plymouth in 1623 by Mather the Elder. In it, he gave special thanks for a devastating smallpox plague that wiped out most of the Wampanoag Indians who had helped the Puritan community.[6]

Celebration of Thanksgiving ensures that the European invasion of North America and the genocide against its original inhabitants remain invisible. Native peoples remain stereotyped, marginalized and exploited. Thanksgiving is a time of mourning for many Native Americans and their allies.

- via Coca Cola Christmas Art

Christmas

Similar to St. Valentine’s Day and Halloween, Christmas began as a thinly veiled attempt to place a Christian overlay on Winter Solstice celebrations common throughout the Roman Empire. Christmas has a checkered history and was never a particularly spiritual holiday. The noisy and festive celebrations brought over from England by non-Puritan colonists were so unsettling to the Puritans that they banned them. In fact, many of the dominant religious churches in the colonies did not celebrate holidays such as Christmas. [7]

Even into the 17th century boisterous festivities marked the holiday. In the late 19th century Christian male elites such as the Knickerbockers – a group of New York gentlemen – began a systematic process of domesticating the holiday by moving its celebration from the rowdy public to a more quiet home setting. The people most influential in establishing Christmas as we know it now were writers: Washington Irving [8], Charles Dickens [9], Clement C. Moore [10], Francis Church [11], Thomas Nast and Queen Victoria [12], through her very public celebrations of the new Christmas [13].

North America’s traditional Christmas was created during this late 19th century period. People were moved off the streets and into churches and family gatherings, where everyone was encouraged to give gifts to children. The rise of department stores and advertising during this time further commercialized and managed this holiday. There have periodically been campaigns to “put Christ back in Christmas,” but in fact he was never really there.

However, authoritarian values normalizing reward and punishment for good and bad behavior, the watchfulness and judgmental nature of God are memorialized in the verses of “Santa Claus is Coming to Town”:

You’d better watch out,

You’d better not cry,

Better not pout,

I’m telling you why

Santa Claus is coming to town.

He’s sees you when you’re sleeping,

He knows when you’re awake.

He knows if you’ve been bad or good

So be good for goodness sake.[14]

Although one is fat and jolly and the other is lean and serene, the similarities between Santa and Jesus/God are striking. They are both all-seeing and all-knowing, both reward or punish behavior (even thoughts), both are portrayed as living in pure white lands with assistants (elves and apostles), both are immortal, accept prayers (and letters) that pledge good behavior in return for favors, perform miracles (bottomless bag of toys/loaves and fishes) and are claimed to be universal in bringing good things to all people. [15] Although Christmas was recreated as a secular commercial holiday in the 19th century, Christian values remain not far below the surface.

During the Christmas season, calendars, school activities, public displays, constant advertising and the media all convey a message that everyone else is not quite American if they celebrate “exotic” holidays such as Chanukah, or more recently, Kwanzaa.

New Year’s Eve

New Year’s Eve/Day is clearly a Christian holiday. The central figure of Christianity is publicly acknowledged to such an extent that history itself and the entire yearly cycle are centered on his birth. [16]

New Year’s day for Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Chinese, Vietnamese, Mayans and many Native peoples happens at other times of the annual cycle, according to other calendars. The fact that western countries imposed this calendar worldwide, even though those in the West are a minority in the world, is never acknowledged.

At the same time, non-Christians operate simultaneously with a second, culturally specific calendar and a set of celebrations and calibrations that guide their community life. Many of these calendars are lunar-based and have a very different rhythm than the solar-based Christian one. And yet we say “Happy New Year” as if this calendar were universal, and we might say “Happy Chinese New Year” or“Happy Jewish New Year” to note these other calendars are culturally specific.

There are many efforts to reclaim some holidays and to abandon others. Multiple cities have proclaimed Columbus Day Indigenous People’s Day, sponsoring education and alternative activities. Throughout the Americas there are Dia de la Raza festivals not only protesting Columbus Day activities, but also celebrating the survival, cultures, land claims and diversity of Indigenous peoples. Native Americans and their allies have organized indigenous celebrations around both Columbus Day and Thanksgiving. [17] People of the Wampanoag nation and their allies in the Plymouth area have declared Thanksgiving a Day of Mourning and hold alternative activities. For several years in Oakland, CA, Native Americans and their allies have hosted a Thangs Takin pre-thanksgiving event. They currently organize a day of protest against the post-Thanksgiving shopping that occurs at a mall built on a Native American village site and cemetery. Some Christians try to avoid the commercialization of Christmas and to infuse the holiday with an alternative set of values.

The holidays we celebrate and the ways in which we choose to celebrate them reveal the values we uphold and pass on to our children. The choice is ours. Christian hegemony operates through the holiday cycle; yet we each have the ability to challenge its impact and gather with others to celebrate our diverse families and multicultural communities. We can do this with simplicity, creativity, joy and much fun.

1 Dahr Jamail and Jason Coppola. “The Myth of America.” Truthout website, October 12, 2009. [online]. [cited September 25, 2012]. truthout.org/1012091.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Chuck Larsen. “There Are Many thanksgiving Stories to Tell,” in Doris Seale et al. Thanksgiving: A Native Perspective. Oyate, 1998.

5 For example, the thanksgiving celebration after the massacre of Pequot men, women and children at Mystic Fort. For more details see Judy Dow. “Deconstructing the Myths of ‘The First Thanksgiving’.” Oyate website, revised June 12, 2006. [online]. [cited October 24, 2012]. oyate.org/index.php/resources/43-resources/thanksgiving.

6 Chuck Larsen. “Teaching About Thanksgiving: An Introduction for Teachers.” Fourth World Documentation Project, 1987. [online]. [cited December 2, 2012]. 2020tech.com/thanks/temp.html.

7 Max A. Myers. “Santa Claus as an Icon of Grace,” in Richard Horsley and James Tracy, eds. Christmas Unwrapped: Consumerism, Christ, and Culture. Trinity Press, 2001, p. 197. In Massachusetts a five-shilling penalty was imposed on anyone found feasting or shirking work on Christmas Day.

8 Irving’s Knickerbocker’s History of New York invented the figure of Santa Claus, and his Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon portrayed a Christmas feast that set the standard fare to today.

9 Dickens toured extensively throughout England and the United States reading his story “A Christmas Carol” to enthralled audiences.

10 Slave owner Moore wrote “’Twas the Night before Christmas.”

11 Francis Church wrote one of the most famous newspaper editorials of all time “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” in 1897.

12 Queen Victoria’s family (but very public) Christmas tree was romanticized in the popular media, and Christmas trees became essential components of every Christian family’s celebration.

13 For more details see Tom Flynn. The Trouble With Christmas. Prometheus, 1993, pp. 96-108.

14 Lyrics and music 1934 by J. Fred Coots and Haven Gillespie © EMI Music Publishing.

15 See Flynn, The Trouble with Christmas, pp. 139-40.

16 The Romans eventually settled on the Julian calendar that had January 1st as the start of the year, but many European countries used other annual starting dates, most prominently March 25th, the day of the Annunciation. It was only during the 16th century when Pope Gregory XIII officially set the Gregorian calendar (1582) that most Christian countries aligned their annual cycles with a January first start date. England only moved New Year from March 25th to January 1st in 1752.

17 One of the most noteworthy events are the sunrise gatherings held on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay every year on both holidays in commemoration of the takeover of the island by Native American activists in the 1970s.