The following is excerpted from Living in the Shadow of the Cross: Understanding and Resisting the Power and Privilege of Christian Hegemony, by Paul Kivel.

The language we use is an indication of the deep structures of the way we think. The vocabulary, phrasings, and both explicit and implicit meaning of English words and concepts reflect our long history and the influence of many cultures, religions, and ideas of both dominant and resistant groups.

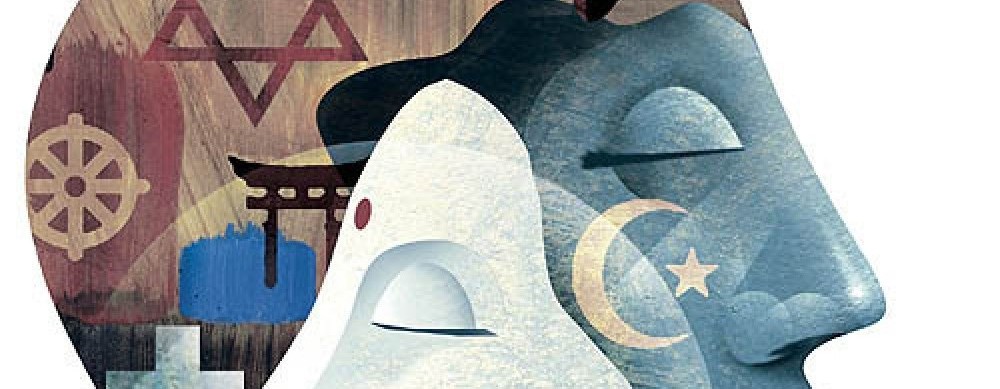

One of the longest-standing systems of institutionalized power in the United States is the dominant western form of Christianity that came to power when the Romans made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. Christian hegemony—the everyday, pervasive, deep-seated, and institutionalized dominance of Christian institutions, Christian leaders, and Christians as a group—has profoundly shaped our lives. Some of that influence is very visible in our laws, customs, beliefs, and practices. Other parts of that influence have become nearly invisible, secularized, “common-sense” forms of knowing and being in the world. One way to identify both levels is to examine our language and the ways it represents, reflects, and reproduces Christian dominance.

When presented with Antonio de Nebrija’s Spanish Gramatica, the first-ever grammar of any modern European language in 1492, Queen Isabella reportedly asked the scholar, “What is it for?” Nebrija reportedly answered, “Language is the perfect instrument of empire.”[1]