The Western economic system, what we now call capitalism, grew out of a Christian culture whose prime focus was individual salvation and the fulfillment of God’s plan.

In the 13th century, the Church declared that only those who voluntarily renounced wealth to become poor were deserving of charity. Renunciation was labeled a sign of rejection of the comforts and temptations of the material world and of a person’s humility before God. The Church designated those who were “just poor” as unworthy of assistance and possibly sinful. Thus, the concept of the deserving poor justified denying most people any form of social support. There was no longer any moral reason for individual Christians or civil institutions to feel obligated to take care of those in need; it became easy to blame people for their poverty as an excuse for not assisting them.

Over the next centuries the European ruling classes ravaged the peasantry with enclosures and drove people off the land into towns and cities where there was little work. In response to peasant protest, poor laws were passed in England and elsewhere to provide basic subsistence for people living in poverty. Joseph Townsend, one of the strongest proponents of eliminating the poor laws wrote, “The Poor Law regime should be removed…because it tends to destroy the harmony and beauty, the symmetry and order of that system, which God and nature have established in the world.”1

Basically he was saying that God’s economy provided a natural incentive to people to work – hunger – and any intervention would only undermine its beauty and purpose. If the government provided for those in need it would hinder their development of the virtues of hard work, frugality and abstinence and promote sloth and immorality.

Protestantism further entrenched these beliefs by emphasizing personal choice and assuming God rewarded (or at least appreciated) hard work and moral behavior (and the more one worked the less time one had for immoral behavior). Enlightenment philosophers contributed to the justification of capitalism by asserting an unregulated (so-called free) market economy would automatically move society toward a prosperous state. A just and benevolent God or, as professor of natural theology and economist Adam Smith put it, an invisible hand virtually guaranteed such a result unless governments interfered.

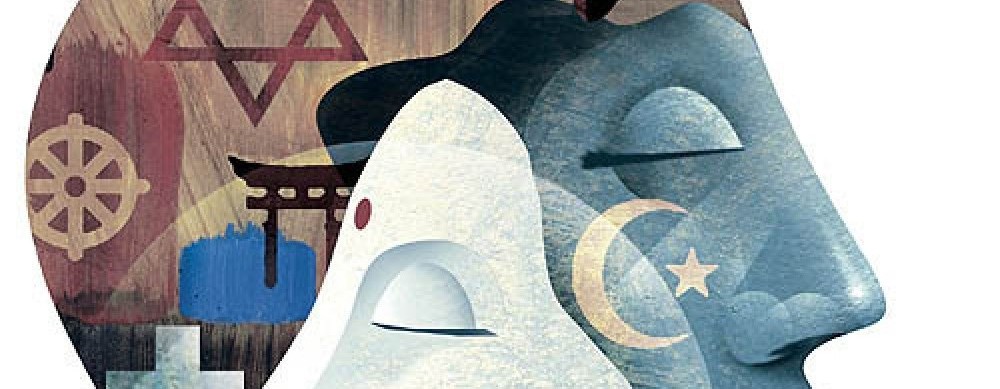

The other lynchpin of our Christian/capitalist economic system is the theory of the rational economic actor. Based on an imagined white Christian male who makes rational choices in the marketplace, this model is used to justify economic policies. The economic actor is the same as the individual moral actor in dominant Christianity: completely independent, self-centered and without dependents. If he makes bad choices, the fault lies only with him, not with the socially and economically constructed choices he may face.

Today, personal discipline, rational choice and the morality of the market are still highly touted by popular economists such as Frederick Hayek, who wrote in his article, “”The Moral Imperative of the Market,”…people must be willing to submit to the discipline constituted by commercial morals.” Such statements reinforce beliefs about individualism, hierarchy and discipline in economic language.2

Despite long-standing historical evidence that an unregulated economy leads to widespread poverty, harsh working conditions, consolidation of wealth and power and severe levels of environmental degradation, such an economy continues to be championed by many as a natural and progressive system that grants everyone the equal opportunity, i.e. choice, to succeed or fail in the market. It inevitably benefits everyone who works hard and punishes those who don’t.

In the US we live in a vast, interdependent economic system in which the concentration of wealth among the few produces environmental destruction, shorter life spans and deteriorating health for rich and poor alike – a quality of life that lags considerably behind almost all other over-developed countries. Our challenge is to reject long-standing and punitive dominant Christian morals by envisioning and building an economic system that distributes wealth based on mutual support, cooperation and a commitment to meet people’s basic needs.

Resources

[1] David Noble, Beyond the Promised Land, p. 100.

[2] Quoted in Jay Youngdahl. “The Fuzziness of Human Rights: On the anniversary of its legal birth, the concept is losing its interpretive luster.” East Bay Express, March 4-10, 2009. p. 5. [online]. [cited December 12, 2012]. eastbayexpress.com/ebx/the-fuzziness-of-human-rights/Content?oid=1176832.